Unseen Threats: Local Vulnerabilities and the Strategic Threats Lurking in National Critical Functions

By Charles Harry, PhD, Director, Center for the Governance of Technology and Systems (GoTech), University of Maryland

In March of 2023, the Biden administration unveiled its highly anticipated cyber strategy, a policy aimed at confronting the ever-growing challenges posed by a world teeming with insecure devices. The approach, largely inspired by the Solarium Commission report, seeks to shift the burden of security away from end users and onto vendors, recognizing the sheer scale of the problem and the dire lack of cybersecurity measures across various industries and consumers. However, this approach merely scratched the surface of governments’ true conundrum in safeguarding their populations.

While insecure devices can represent a private problem leading to loss of data or support to a key organizational process, the public concern is that those systems support services critical to modern society. For example, an attack on the software reservations system at a large national airline that leads to a disrupted system is both a problem for the airline, who suffers delays and financial consequences, as well as for policymakers concerned about the larger scale impacts on the air transport system itself. Interdependent organizations and systems form the basis of so called National Critical Functions (NCF), and they serve as the basis for national risk management discussed at length in both the Solarium Commission Report and serve as a core assumption in the Biden cyber strategy.

We find ourselves in a world where countless organizations, each with their own unique critical systems, intertwine and rely on one another to support any number of specific NCFs. It is within this intricate web of devices, systems, and processes that threat actors seize the opportunity to wreak havoc, unleashing potentially catastrophic consequences not only to specific technical systems and organizational processes, but also to society. Look no further than the Colonial Pipeline attack, where nearly half of the East Coast’s gasoline supply was decimated for several days, or the NotPetya event that brought seven of the world’s largest terminals to a grinding halt, causing logistical nightmares across North America and Europe. The water treatment facility in Oldsmar, Florida, and the electric grids in Ukraine and South Africa have also fallen victim to the same set of strategic challenges. These vital systems are predominantly owned and operated by private firms or local governments, but whose compromise and disruption further complicate the federal government’s ability to measure and monitor strategic risk.

Our study categorized four areas of concern: services prone to denial-of-service attacks, illicit access to data through SQL injection attacks, unauthorized network access via brute force, including remote desktop protocol, and the abuse of file sharing protocols like SMB.

So, how does the federal government assess and manage this collective challenge? Perhaps an example would help answer this question. The networks of county governments support many core services afforded to citizens. Therefore, the vulnerability to those systems is important to assess not simply as a set of isolated islands, but more so systematically and across multiple geographies. Given the desire to assess national risk, how do we gauge the extent of the problem and assess the cybersecurity preparedness of local governments that directly impact the lives of everyday citizens? The truth is that our understanding of the holistic security posture at the county government level is alarmingly limited.

Sparse research, often hindered by abysmal response rates, has shed light on the general lack of cyber preparedness within county governments. This raises crucial questions about the potential fallout if these vital infrastructures were to come under attack, jeopardizing the very services on which the population depends. At the Center for the Governance of Technology and Systems (GoTech), a research center at the University of Maryland, we recently attempted to explore these themes seeking to quantify the challenges faced by state and federal policymakers responsible for protecting our critical functions within county services.

Our study aimed to quantify the size and severity of the threats lurking within these indispensable systems by employing a fundamental technique utilized by cybersecurity professionals: enumerating attack surfaces. While this method is commonly employed to understand and mitigate potential vulnerabilities within individual networks, integrating multiple attack surfaces across geographies has not been employed for the purpose of strategic assessment to assess and manage vulnerabilities on a national scale.

Malevolent groups, including criminal organizations, nation-states, and hacktivists, have exploited any number of devices by abusing specifically exposed services. These include attacks by the Mirai botnet on exposed DNS to unleash devastating denial-of-service attacks, as well as criminal groups utilizing SQL injection attacks to exploit exposed MySQL instances, or even brute forcing attacks on exposed RDP. Consequently, the number of devices and their vulnerable services directly impact the attack surface across all systems tied to county government services. Of course, just because a service is exposed (e.g., SSH) means it can or will be attacked. However, it can still represent a concern that deserves to be evaluated and potentially mitigated to reduce the probability of a future compromise.

But just how dire is the situation? Our study reveals that county governments mirror the communities they serve. Some counties, boasting diverse and populous regions, harbor hundreds of devices and a plethora of digital services at their constituents’ fingertips. On the other end of the spectrum, smaller counties house a meager digital infrastructure, if any at all. Our report delves into the evaluation of over 3,100 county governments, encompassing 99% of all U.S. County government networks. Through our approach, we identified over 26,000 devices, unraveling a complex tapestry of deployed digital services across the nation.

On average, each county possesses a relatively modest number of devices, standing at 8.53. However, this average is skewed by the inclusion of large counties, with one particular county in the United States exposing a staggering 870 devices. The median value of 3 devices per county highlights the relatively small attack surface of most county governments, with a smaller set of counties deploying larger amounts of digital infrastructure. Furthermore, our evaluation of open ports and exposed services unveiled that those counties, on average, leave over 66 ports vulnerable across their deployed systems. Understandably, infrastructure varies significantly across states and regions, with rural counties deploying fewer systems and their urban counterparts embracing a more extensive digital landscape. Yet, despite the size of the attack surface, which is predominantly shaped by densely populated areas, the vulnerability of these systems to known exploitable services is a nuanced matter.

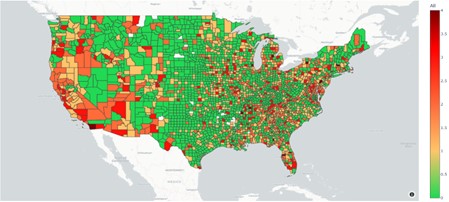

Our study categorized four areas of concern: services prone to denial-of-service attacks, illicit access to data through SQL injection attacks, unauthorized network access via brute force, including remote desktop protocol, and the abuse of file sharing protocols like SMB. While states housing major population centers, such as New York and California, undoubtedly face significant exposures to these problematic services, it is worth noting that other states, like Tennessee, also harbor numerous counties vulnerable to exploitation. Our findings reveal a stark range of severity, as depicted in the figure below, with levels of concern color-coded on a five-point scale, ranging from zero (low) in green to four (very high) in dark red.

The severity of potential concern of exposed services across regions is nothing short of alarming. Countless counties find themselves susceptible to multiple attack vectors, demanding immediate attention. This comprehensive view of severity across all counties underscores the strategic risks meticulously detailed in both the Solarium Commission report and the U.S. Cyber Strategy. The diversity in size and potential vulnerability of these systems presents a collective problem that the federal government cannot ignore. The pressing question arises: How can the government effectively manage such a diverse array of infrastructures when it lacks direct control over them? In the face of newly discovered exposed services, how can cybersecurity officials at CISA swiftly identify, communicate, and assist local governments or private operators in resolving problems as they are identified?

If the U.S. government wishes to fulfill the goals outlined in the Solarium Commission report and the U.S. Cyber Strategy, it must contextualize technical vulnerabilities within a strategic framework. While CISA possesses a well-developed framework for national critical functions, mapping the intricate web of organizations and their interdependencies remains a critical task. Without this comprehensive mapping, scans, penetration tests, and other techniques will remain isolated and fail to provide policymakers and business leaders with the necessary context to prioritize defense investments. Policy documents may paint an inspiring vision, but connecting these systems to the human functions they support is the true solution.

Although it involves mundane and intricate work, mapping the organizations within government, industry, and geographical context is an absolute necessity to grasp the problem holistically. Only then can we hope to meet the objectives laid forth by our policymakers.

Dr. Charles Harry is the Director of the Center for the Governance of Technology and Systems at the University of Maryland, College Park. Prior to his appointment at the University, Dr. Harry was a senior official working in cyber operations within the intelligence community.